Total number of posts 463.

As global trade undergoes a major shake-up under Trump 2.0, Southeast Asia is looking for ways to stay resilient. One promising path lies in boosting trade in services — but experts warn that unless ASEAN countries harmonise regulations and curb protectionism, the region’s service industries will continue to struggle to expand across borders.

ASEAN Looks to Services for Growth

At the ASEAN Leaders’ Summit held in May 2025, Singapore Prime Minister Lawrence Wong urged member states to look “beyond trading in goods” and accelerate trade in services, which he called an equally vital part of the economy. The leaders agreed to enhance the competitiveness of their services sectors and facilitate more intra-ASEAN trade.

Yet despite such commitments, few companies have managed to grow across borders. Even in economies where services already account for over half of GDP — like Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand — many firms remain confined to their home markets due to cultural, regulatory, and structural barriers.

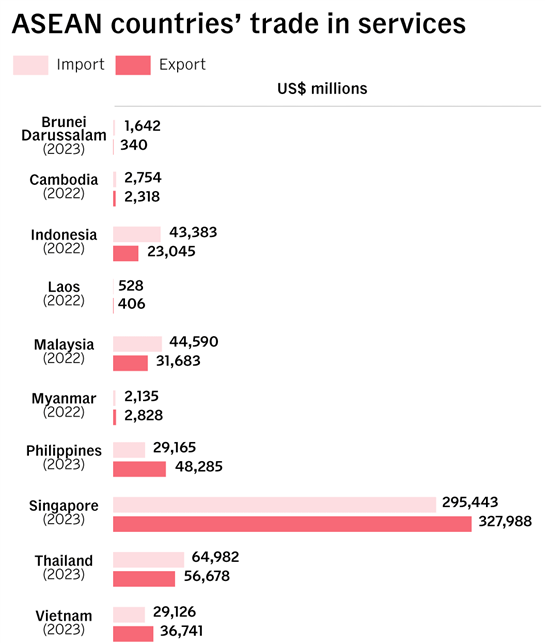

Source: ASEANstats

ASEAN’s services trade remains modest compared to its trade in goods. In 2022, total services trade reached US$933.6 billion, with only 13.3 per cent conducted within ASEAN. By contrast, intra-ASEAN goods trade accounted for 22.3 per cent of the region’s US$3.8 trillion total. Singapore dominated the services sector, accounting for nearly 59 per cent of the region’s total.

Only the Philippines, Singapore, and Viet Nam recorded surpluses in services trade in 2023, while the other seven members imported more than they exported — often from non-ASEAN partners, in sectors such as education, IT, finance and healthcare.

“Opening up the services sector offers huge potential for the region,” said a spokesperson from HSBC Global Investment Research. “Unlike goods, there are no tariffs on services — the real barriers are regulatory.”

Regulatory Fragmentation and Structural Barriers

Experts point to deep-rooted challenges, from fragmented regulations and uneven infrastructure to differing legal systems and skills gaps.

Each ASEAN country maintains its own tax codes, ownership rules, and data protection laws, making regional business expansion complicated and costly. Mutual recognition of professional qualifications also remains limited. For instance, certificates issued by an Indonesian company might not be accepted by Singaporean clients, even if they come from the local branch of an international firm.

Cross-border hiring is equally burdensome. Immigration and work permit procedures vary widely, discouraging mobility of skilled workers.

Protectionism Persists

ASEAN has long recognised the need for a more open services market. The bloc has adopted frameworks such as the ASEAN Framework Agreement on Services (AFAS), the ASEAN Trade in Services Agreement (ATISA), and the ASEAN Services Facilitation Framework (ASFF).

On paper, these aim to promote freer movement of capital, skills, and services. In practice, implementation has been uneven, and protectionist tendencies remain strong.

For example, Thailand reserves certain occupations such as hairdressing and woodworking for her citizens only, and Indonesia maintains foreign ownership limits and nationality requirements in sectors such as insurance.

“Domestic conglomerates still dominate most service industries, from manufacturing-linked logistics to finance,” said Pavida Pananond, professor of international business at Thammasat University. “That makes it hard for startups and regional challengers to grow.”

She noted that Thailand’s approach to digital banking illustrates this imbalance: “The government prefers established banks expanding into digital services rather than supporting disruptive newcomers.”

This protectionist environment leaves few opportunities for cross-border growth. Firms that do expand often rely on mergers and acquisitions to enter new markets, since adapting to different consumer behaviour, purchasing power, and regulations across ASEAN can be prohibitively difficult.

Mixed Incentives Among Members

The 46th ASEAN Summit closed with calls for faster implementation of existing agreements. But experts say that enthusiasm for liberalisation is uneven.

“Not all member countries see themselves benefiting from opening up services,” said Teuku Rezasyah, an international relations expert from Indonesia’s Padjadjaran University. “Some view liberalisation as a threat rather than a safeguard against tariff wars.”

Laos, for instance, has been hit with a 40 per cent US tariff on its goods - the highest in the region. Despite a US$700 million goods trade surplus with the US last year, the country’s services sector remains small, exporting just US$406 million in 2022, according to ASEAN Secretariat data.

Such disparities explain why only stronger service economies like Singapore and Malaysia consistently push for deeper integration.

Lessons From Europe

ASEAN’s progress in integrating services has taken a different path from the European Union’s approach, which has focused on harmonising standards and enabling the free movement of professionals.

The EU not only removed tariffs and quotas but also established common regulations and mutual recognition of qualifications, backed by strong enforcement through the European Commission and the European Court of Justice.

“ASEAN’s consensus-based approach makes it impossible to replicate the EU model entirely,” Teuku said. “But elements such as recognising each other’s standards and professional certifications could be adopted.”

Other regional blocs are already moving in that direction. Latin America’s Mercosur and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) are exploring similar integration efforts, which could outpace ASEAN and attract more investment.

The Way Forward

Despite the challenges, experts and businesses agree that solutions are within reach. Streamlining business licensing, facilitating cross-border projects and exploring regional capital market integration are all seen as practical steps.

Private firms also have a key role to play. “Progress won’t only come from government agreements,” said one expert. “Market-driven initiatives are already pushing integration forward.”

For example, Singapore-based e-commerce platform Shopee has launched its “Shopee International Platform,” allowing merchants in one ASEAN country to sell directly to others. Similarly, fintech and logistics startups are forging partnerships to overcome regulatory hurdles and expand their reach.

Bhima Yudhistira, executive director of Jakarta’s Center of Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS), believes the region’s service sector could be ASEAN’s “untapped growth engine.”

“Developing a stronger services economy would help ASEAN diversify beyond manufacturing and shield itself from external shocks like tariff wars,” he said. “But achieving that requires what ASEAN often struggles with: moving beyond rhetoric to real reform.”

Bhima suggested that countries start by building on their strengths, such as tourism and hospitality in Thailand, financial services in Singapore, and logistics in Indonesia.

“The question now,” he said, “is whether Southeast Asian countries are ready to set aside their differences and get serious about full integration.”

Source: Channel News Asia (CNA)